The first portrait I ever drew was of my grandmother.

I was about four or five years old. It had been just me and Ajji at home. It was a little before lunchtime, when the house would smell of ash gourd saaru and thuppa, and rice huffed away in several cookers across the neighbourhood. The air was redolent, charged with getting things in order before the hungry crowd came home for lunch.

I don’t remember the particulars, but it is likely I was pestering Ajji for a lunch-cancelling snack. My favourite at the time was a fistful of hurgaDale, sugar and grated coconut/copra, something I ate with alarming frequency alongside mainlining palmfuls of spit-wet Bournvita. Having this far survived a plum 60-year life of nonstop child-origin bullshit, my frankly fed up Ajji gave me the only spanking she has ever given me. I remember being surprised, then wanting to come across as strong, unfazed — and my pride finally shattering when I couldn’t help but cry. Leaning fully into my bawling, I had slow marched back to our room, rubbing my behind. My frock’s bow had come undone and the ribbons had been trailing. I was hiccuping, my nose ran freely, my eyelashes were in clumps.

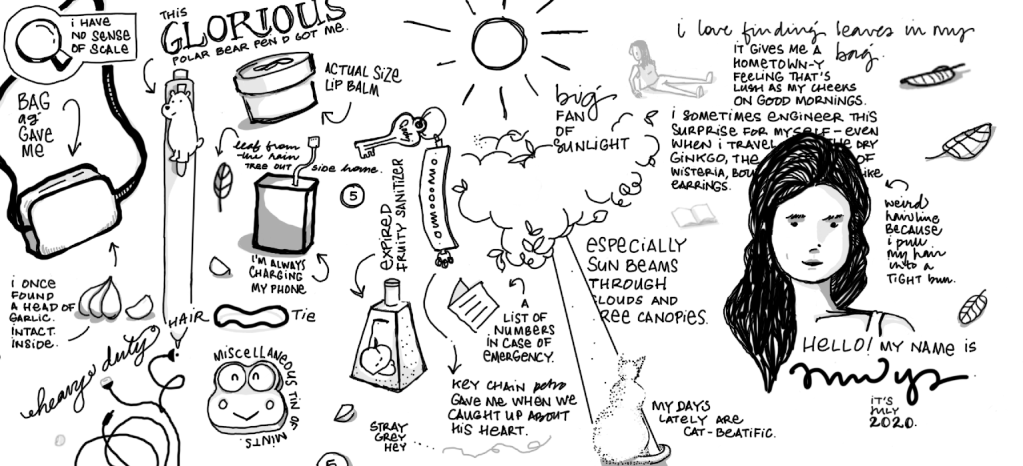

By then, I’d been used to placating myself while crying. Away from observing eyes, I would tire quickly and would instead engross myself with how teardrops were shaped, the sensations I’d feel when I’d squeeze my wet eyes, the oddities of my toes. There was always something to see, something to look at closer, something to commit to memory. My breath would steady to a snotty mouth-breathing while I amused myself with the universe of details that everyday brought:

Ajji’s funny burp while she sat on the sofa with her fissured feet up on the teapoy, somedays doing the Kannada crossword directly in pen. Ajji’s nose. The small waves of Ajji’s hair. The print of her saree, how it looked when I eagle-armed swooped down on her lap and closed my left eye, then closed my right. I could bury my nose in its worn-to-tuft cotton and take a walk through the grove of her days: the washline, the rexona bath, flowers at every doorstoop. The garden, the store room, her groaning godrej bureau. My grandfather’s vest, my grandfather’s sofa-doily, my grandfather’s off-to-work handkerchief.

There were so many places to go wandering with my mind. On this eventful day, I’d gone wandering with a green crayon, all along our recently-painted cream-yellow wall.

The next part of this memory features me and my extremely angry mother looking perfectly pitiful. We’re scrubbing the bedroom wall with the kitchen sponge and a trough of soap water, hoping to undo my first ever portrait, mural, public artwork, and act of vandalism:

A sunflower, standing in its pot, leafy hands on its hips. It’s a female sunflower with two nose-studs, and hair worn in an Ajji-style bun. It is an angry all-green sunflower, and it’s screaming at an otherwise sunny and totally green landscape of house, garden, mountains, river, birds.

Portraits are about subjects, but also about what a painter feels about their subject. An electric meeting of two viewpoints: of watching, and being watched.

Ajji lived a long and full 85 years. Her life was so full of stories and each story was a two-palms large pomegranate brimming with bright red rubies that I could spend all of my life just drawing and writing about.

It amazes me even now — after haggling with the hearse in the middle of a pandemic, after tearfully whispering goodbye to her ashen bones — how nothing, not death, not the indignity of disease, not the acrid smog of grief, has truly been able to eclipse my Ajji’s sunniness in my mind.

On winter mornings and evenings, my dolled-in-the-sweater-I’d-bought-her Ajji would sit, powdery chinned, flowery haired, smelling like home itself, on the sofa in our verandah. Her arms would be suspended over the armrests of her seat, her glass bangles tinkling their way down. Her small torso would be sitting upright, eyes mostly shut, feeling the sun play on her face and back.

Everything twinkled in this light. Her nose-stud. The apples of her gigglesome cheeks. The silver of her hair. Her gently blinking eyelashes. A soft, diffused halo would spread around her mostly white and shiny head.

Ajji would catch the sun and hold it in her face like a giddy flower in spring. She just couldn’t help herself. Like a child off to play on a surprise-holiday. She’d show up and take it on the chin, everything, every perversion of chance that life threw at her, and she looked forward to at least… a sunbeam. It was her smallest, most private meditation thanking life’s rare ability to be kind. At least a sunbeam kind.

I see why my grandfather’s rocking chair was poised opposite her sun-seat.

In her last decade, Ajji’s life was upended in Parkinson-tempests. With every stroke after pin-prick stroke, we watched her mind retreat into her slowly locking-itself body. But we were also lucky. We snatched months, weeks, then days, hours, then tv shows, boxes of sweets, and rolls of monaco, then mere minutes with her, when she’d be here. When she’d ask me why I hadn’t yet dyed my hair, or say something that sounded like a hello and a goodbye, till one day she’d just set her eyes on me, and only the flicker of a sunbeam passed her faraway eyes.

I miss Ajji very much. I miss her bubbling, belly-bobbing laughter. I miss her bELE saaru. I miss how much she loved me, how much she loved us, how much she loved a simple thing like soft winter sunshine.

My Ajji.

1935 – 2020.